Afghan activist Gaisu Yari reflects on her trip to South Africa, where she found allyship in a shared struggle for freedom and learned important lessons from the country’s history of resistance.

In April, I joined a delegation of Afghan women leaders travelling to South Africa, a trip organised by Malala Fund and its partners, to build alliances with activists, human rights leaders and legal experts who helped end apartheid in their country. I will never forget the moment I landed in the country, my heart heavy with the loss of Afghanistan, my homeland, to the Taliban. But as I stepped onto South African soil, rich with the echoes of its struggle against apartheid, something shifted inside me. I realised that my sorrow could no longer remain passive. It had to become something more, something that could fuel the fight for freedom and liberation.

I also noticed certain parts of my brain, my imagination and my thinking awakening after being inactive for so long. One thought deeply stood out: how could we have ignored the leadership of the Global South in our fight to dismantle gender apartheid for so long? I began to reflect and understand how the Global North has framed women in Afghanistan — too often reducing us to victims, our agency stripped away and categorised based on other nations’ political interests.

Connecting through shared struggle

Later, I began thinking more positively about how it is still not too late to focus on those who have been sharing similar struggles and pains. South Africa triggered memories of losing my father at the hands of the Taliban, but it also gave me and the other women the opportunity to meet, share with and listen to people who lived through systemic oppression not too long ago. South Africa was the perfect place to begin a journey of solidarity.

Sitting with jurists, experts and activists as part of a roundtable at the Nelson Mandela Foundation, there was one important aspect: when I shared personal experiences of our struggle and the stories of how women have been living under a gender apartheid regime in Afghanistan, I noticed these leaders’ humbleness alongside their close familiarity with the subject. They never made me explain myself over and over. It allowed me to show my vulnerabilities, speak on our long-lasting struggle and maintain hope for future collaboration.

Visiting Constitution Hill, where ordinary people and many of South Africa’s leading activists were imprisoned, and engaging with the media and public, I felt and understood that while apartheid may have officially ended, it continues to shape lives and power structures in the country today. The echoes of its painful past and the fight for justice that accompanied an ongoing struggle for equality are visible in their communities. South Africa’s history of resistance taught me that even when oppression seems overwhelming and the road ahead is very long, the fight for freedom is not only necessary, it is always unfinished.

Documenting and telling our truth

Visiting the Nelson Mandela Foundation reminded me of what we missed in Afghanistan between 1996 and 2001: documenting and prioritising women’s voices and lived experiences through our rich tradition of oral storytelling, and curating these narratives to shape and support the women’s movement in our country. We repeated this error for more than two decades from 2001 to 2021. Recording the voices of women from the grassroots could have helped us take a more comprehensive approach and break away from the traditional advocacy methods we were compelled to adopt.

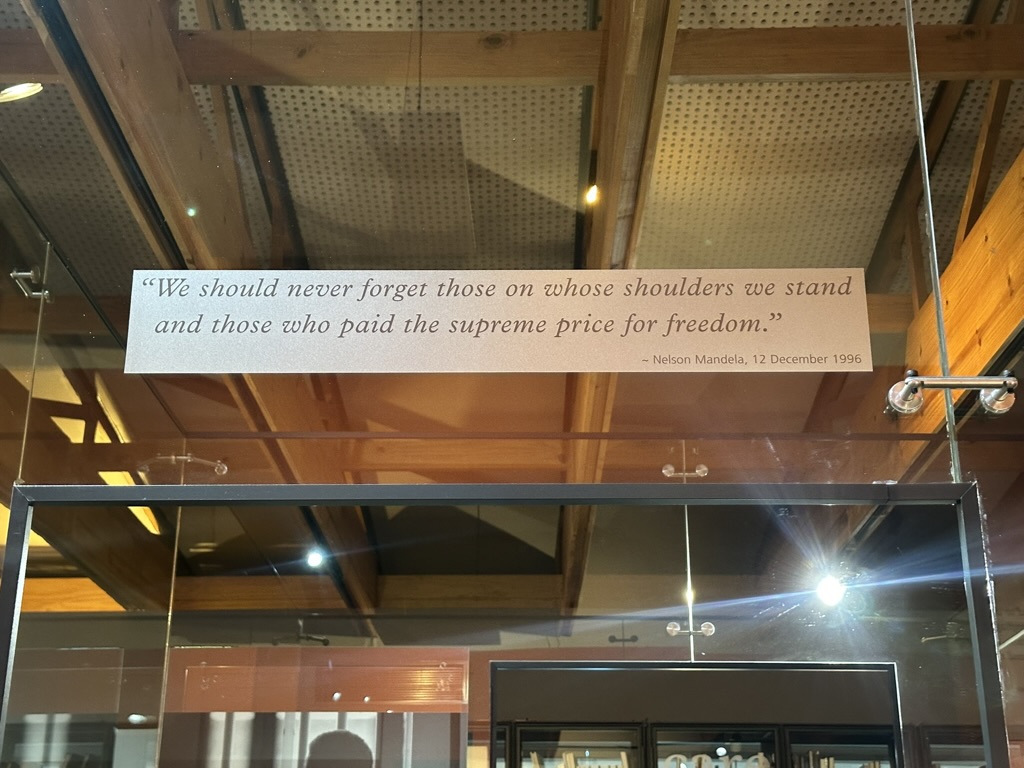

Reading one quote after another on the walls of the foundation’s building, I felt both emotional and deeply moved by the realisation that we still have so much to do and so much to learn. We must be humble enough to acknowledge what we have missed because that admission is a strength, not a vulnerability.

By the end of each day, I returned to my computer and reviewed stories of women in Afghanistan that I have been documenting since the Taliban takeover in 2021. At one point, I played a voice from Ghazni province that filled my hotel room: “If I had the opportunity for the world to hear my voice, I would want them to truly understand us, to hear the pain and struggles of women and girls. What I wish for the women of Afghanistan is the right to make their own decisions, the freedom to live as they choose and the right to education. These are basic rights we were meant to have — but right now, we don’t have any of them.”

I moved to another voice, its plea just as urgent: “I especially call upon the women of the world to stand in solidarity with women of Afghanistan, helping them find a way to achieve their dreams and goals. Right now, many talented girls in Afghanistan have been forced to abandon their education and freedom, leaving them hopeless. Many have been forced into early marriages or experience private imprisonment.”

These stories are essential to record so that we have control over our own fight and how we define ourselves. While the Taliban are controlling women in public and private spaces, women are showing us their commitment to resistance.

As we concluded the discussion at the Nelson Mandela Foundation with South African activists and experts, I understood something profound: this grief, our grief, could not remain a private sorrow. It had to be transformed into action. Our pain fuels a collective movement for justice. We cannot afford keeping those experiences within us. We must tell the truth of what it means to live under gender apartheid.

Confronting colonial legacies

Our movement must also confront how colonial thought patterns have shaped traditional forms of advocacy across global platforms. Too often, we remain locked into the belief that our truest allies are those who founded the mainstream global women’s movement — a movement that has historically centred a singular narrative while overlooking the layered, intersectional realities of women in the Global South. We have yet to truly account for the persistent impacts of colonial power in places like Afghanistan. Solidarity cannot be sincere if it fails to recognise how colonial legacies continue to inform not just systems of oppression, but also the very frameworks through which we claim to resist them.

True solidarity must move beyond symbolic gestures or reactive concern from the Global North. It must be grounded in humility, long-term partnership and a willingness to redistribute power. This means listening more than speaking, funding grassroots movements instead of institutions and recognising the leadership already present in the Global South.

The road ahead is long, just as it was in South Africa, and the wounds are still fresh. Keep reading, keep listening and keep understanding because dismantling an apartheid regime isn’t quick work. It can take decades, even generations.